|

| River Colne at North Mymms Park on 29 December 2017 Image by the North Mymms History Project Released under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 |

Hertfordshire’s River Colne flows through the west of North Mymms. During certain conditions, when the swallow holes at Water End are saturated and a lake is formed, the overflow channel feeds the normally dry riverbed of the Colne. Malcolm Tomkins, a prolific local historian who died in 1981, wrote the following article about the river for the June 1966 edition of the Hertordshire Countryside magazine.

The rise and fall of the River Colne

by M. Tomkins

|

The normally dry river bed from Church Avenue. North Mymms

Image by M Tomkins, from the Peter Miller Collection

|

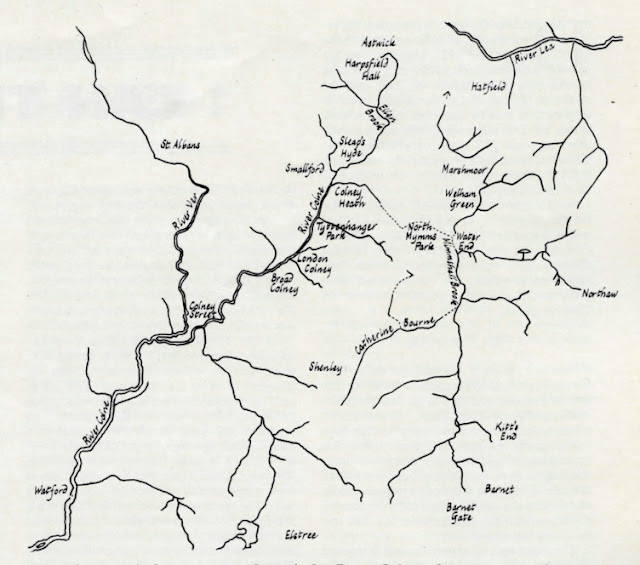

Where does the Hertfordshire Colne rise? Its source has been placed between Barnet and Elstree, near Kitt’s End and south of Hatfield; but it is only occasionally that the streams rising in these parts flow into the Colne. It has also been said to rise in the Chilterns—which is true only of its later tributaries, the Ver, Gade, Chess and Misbourne—and to the west of Hatfield, near Sleapshyde, Harpsfield Hall, and Astwick. The stream referred to here, however, though in its lower reaches called locally the Colne, higher upstream is the Ellen Brook. The Colne is also the name given to the stream that flows across Colney Heath, which is another place named as the source of the river. North Mymms is yet another, while Sir Henry Chauncy wrote in 1700 that it “springs forth near Tittenhanger.”

* * *

The cause of this is to be found a short distance away at Water End, where the waters of two streams, which have grown smaller and smaller as they approached this spot, do indeed seem to end. Once, it has been suggested, they regularly ran on through what is now North Mymms Park into the Colne; but having hereabouts worn away the surface clay and struck the underlying chalk, they found their way down a number of narrow fissures and these, as more and more water trickled through and gradually dissolved the chalk, widened until they formed the well-known swallow-holes.

DISAPPEARS—THEN EMERGES

It has been discovered by the use of colouring matter that some, if not all, of the water that disappears down them emerges up to ten miles away in several springs that run into the Lea. That river has thus captured the water from the streams that run down to Water End, the larger of which is the Mimmshall Brook, which once fed the Colne. Perhaps it would be truer to say that it has recaptured the water, for long before the Mimmshall Brook ran into the Colne it is thought to have run on northwards through Marshmoor to join the Lea near Hatfield. It was in the Ice Age, when that valley was blocked by a tongue of boulder clay advancing from the north, that the waters were diverted along the ice-margin and cut a channel through to the Colne. And although today they normally find their way back into the Lea by the underground channels beneath the swallow-holes this is not always so; when, after heavy rains, these reach saturation point they overflow and a lake collects over them which finds its outlet in the normally dry and grass-grown bed of the Colne below Water End.

RISES SUDDENLY

When this happens there is soon a torrent swirling under Teakettle Bridge by the old Water End school and plunging over the waterfall at the beginning of Church Avenue. In North Mymms Park the river has been known to rise at the rate of a foot an hour; and it was observed towards the end of the last century that “at Colney Heath . . . where for nine months of the year it can hardly lay claim to the dignity of a brook, it is no uncommon occurrence for the petulant stream to rise suddenly to a height of five or six feet.” In the winter of 1878-9 the heath became one vast lake and the twenty-two- foot-long and ten-foot-high brick bridge over the river was swept away. Perhaps it was with this in mind that eight years later a special vestry meeting was held at North Mymms “for the purpose of taking into consideration the best means of preventing the disturbance of the bed of the torrent at the entrance of the Church Avenue, before it injures the foundations of the bridge.”

* * *

After these demonstrations of how full the river could be. round about the turn of the century there was an attempt to turn the channel above Colney Heath into a canal for pleasure craft; but it was doomed to failure, for the water only disappeared into further swallow-holes. As it happened, though Watford High Street was awash again in 1903, it was not until 1936 that floods as bad as those at the end of the century were seen again at Water End. This time it was, unexpectedly, in summer. After a thunderstorm on the afternoon of June 21 in which four inches of rain had fallen the lake at Water End spread across the Barnet by-pass for a width of 150 yards and for over an hour all traffic was held up. Such was the force of the waters that a man who tried to cross a plank bridge by the pumping station was swept away and drowned, while downstream the Colne flooded the fields of North Mymms Park.

|

A map of the upper reaches of the River Colne

showing some of the places named in the article

Image from original article embedded below

|

FURTHER FLOODS

In April 1942 further floods were recorded, and the war land drainage campaign aggravated the problem when it increased the flow of the Mimmshall Brook. But after the swallow-holes had overflowed badly again in 1960 steps were taken to try to prevent future flooding. The Colne, in consequence, overflows less often nowadays; but one can get an impression of what it could be like when over Colney Heath there collects a heavy white mist that looks for all the world like the river in flood.

Was it the reputation of the Colne for suddenly flooding its banks in this way that led Michael Dray ton to write in the seventeenth century that she “feels her amorous Bosom swolne”—or was this a poetical fancy inspired simply by the difficulty of finding any other rhyme for Colne? Perhaps, anyway, his calling it the “crystall Colne” and the “most transparent Colne” was a piece of true observation, for John Evelyn in the same century noticed that it was “ a very swift and clear stream,” as indeed it still is.

* * *

It has, in fact, been claimed that no other river flows so fast into the Thames, and this has been suggested as the reason why it was at one time called the River Quick—a name that looks, however, suspiciously like a corruption of Quethelake, as one branch of the river below Uxbridge was once called. That it has also from of old been known as the Colne is evident from the number of places that have been named after it all the way down to its entry into the Thames— Colney Heath, London Colney, Broad Colney, Colney House, Colney Park, Colney Chapel, Colney Street, Colney Butts, Colhey Farm and Colnbrook.

The Hertfordshire historian Salmon thought, incidentally, that the reverse had happened—that the Colne was named after Colney Street, the place where the Roman Watling Street led ad Coloniam, that is to Verulamium, but this theory has not been accepted by the experts. The meaning of Colne — a common river-name — is not known, but it is believed to be pre-Celtic and older than the name of its main tributary, the Ver.

It is significant that it was not the name of the Ver but of the Colne that was given to the river below the point where they meet, even though the Ver is here if anything the larger of the two streams. When Chauncy wrote, however, that it was “much the greater stream” either the Ver must have been unusually full or the Colne unusually low. It puzzled him that, in spite of being the smaller, “the Colne usurps the glory of her own name,” but the explanation that has been suggested for this is that the Colne was the larger river before it lost the waters of the streams that disappear at Water End down the swallow-holes. When these overflow this can easily be believed, for it then becomes once more a sizeable river, carrying away the waters of the stream that runs south-west through Welham Green and those of the Mimmshall Brook and its tributaries. Of these, one stream rises near Northaw, another—the Catherine Bourne— near Shenley, and another as far away as Barnet Gate.

* * *

At the other extreme, it has been known in a dry year for there to be no water in the Colne almost as far downstream as Colney Street. Its source may thus vary, it has been estimated, by as much as fifteen miles. No wonder, then, that there has been such diversity of opinion as to where it rises. Normally North Mymms Park has perhaps the best claim, but a period of drought or a single thunderstorm may make it anybody’s guess where its source is to be found.

|

| Cover of Hertfordshire Countryside magazine June 1966 |

The original article, from which the text above was scanned, was written by M. Tomkins and published in the Hertfordshire Countryside magazine in June 1966, and is embedded below. The article is from the Peter Miller Collection and was scanned by Mike Allen.

Comments and information welcome

If you have anything to add to this feature, or just want to add your comments, please use the comment box below.