North Mymms almost a thousand years ago

|

| Writing the Domesday Book By Joseph Martin Kronheim (1810–96) in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

In 1086, North Mymms, formerly known as Mimmine, was surveyed by assessors following an order by the king, William the Conqueror. The king wanted a record of how land was distributed (who owned what), and to work out what taxes were due to the Crown. It was to be a detailed survey, listing not only every piece of land, but also every person, and every farm animal, "not even an ox, nor a cow, nor a swine was there left, that was not set down in his writ". The document containing this information was known as the Domesday Book.

Before taking a look at the Domesday Book's short entry for Mimmine, and examining what the survey uncovered, it's worth considering the circumstances that led to the work - known as "The Great Survey" - being commissioned.

To help better understand the context, the North Mymms History Project has studied many online resources. Those resources are acknowledged throughout the piece via links; many, but not all, via Wikipedia.

Two major projects have been particularly helpful. They are the translation of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle by J. A. Giles and J. Ingram, freely available to download and reuse on Gutenberg; and Open Domesday, the first free online copy of the Domesday Book.

All the images used in this piece are released under Creative Commons. Each image can be enlarged by clicking on it.

The reason for the Domesday Book

|

| Drawing of the Domesday book By Andrews, William Released in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Domesday is the Middle English spelling of the word 'doomsday', which means 'any day of reckoning'. The name was apparently applied to the 'Great Survey' because it was considered to be a final authority.

According to the translation of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle by J. A. Giles and J. Ingram, the decision to commission the Domesday Book was taken in the mid-winter of the previous year. This means that the country-wide research and the writing must have taken place within 12 months. The visit to Mimmine by the king's assessor or assessors would have probably taken place in the first half of 1086.

The following lengthy extract from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is for the year 1085, when the decision to survey much of England and parts of Wales was made. We've included it here because it offers an interesting insight into what might have been going through the king's mind when he ordered that the work be carried out.

We have highlighted in bold the part that signals the start of the work undertaken to create the Domesday Book. The various references in the three paragraphs below are from the translated Anglo-Saxon Chronicle text. We've included the original reference links and added the information to the appendices at the end of this piece.

"A.D. 1085. In this year men reported, and of a truth asserted, that Cnute, King of Denmark, son of King Sweyne, was coming hitherward, and was resolved to win this land, with the assistance of Robert, Earl of Flanders; (106) for Cnute had Robert's daughter. When William, King of England, who was then resident in Normandy (for he had both England and Normandy), understood this, he went into England with so large an army of horse and foot, from France and Brittany, as never before sought this land; so that men wondered how this land could feed all that force. But the king left the army to shift for themselves through all this land amongst his subjects, who fed them, each according to his quota of land.

"Men suffered much distress this year; and the king caused the land to be laid waste about the sea coast; that, if his foes came up, they might not have anything on which they could very readily seize. But when the king understood of a truth that his foes were impeded, and could not further their expedition, (107) then let he some of the army go to their own land; but some he held in this land over the winter. Then, at the midwinter, was the king in Glocester with his council, and held there his court five days. And afterwards the archbishop and clergy had a synod three days. There was Mauritius chosen Bishop of London, William of Norfolk, and Robert of Cheshire. These were all the king's clerks.

"After this had the king a large meeting, and very deep consultation with his council, about this land; how it was occupied, and by what sort of men. Then sent he his men over all England into each shire; commissioning them to find out "How many hundreds of hides were in the shire, what land the king himself had, and what stock upon the land; or, what dues he ought to have by the year from the shire." Also he commissioned them to record in writing, "How much land his archbishops had, and his diocesan bishops, and his abbots, and his earls;" and though I may be prolix and tedious, "What, or how much, each man had, who was an occupier of land in England, either in land or in stock, and how much money it were worth." So very narrowly, indeed, did he commission them to trace it out, that there was not one single hide, nor a yard (108) of land, nay, moreover (it is shameful to tell, though he thought it no shame to do it), not even an ox, nor a cow, nor a swine was there left, that was not set down in his writ. And all the recorded particulars were afterwards brought to him. (109)'

The entry in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for the following year, 1086, the year the Domesday Book was being written, is also interesting because it shows the growing control over land, people and income.

"A.D. 1086. This year the king bare his crown, and held his court, in Winchester at Easter; and he so arranged, that he was by the Pentecost at Westminster, and dubbed his son Henry a knight there.

"Afterwards he moved about so that he came by Lammas to Sarum; where he was met by his councillors; and all the landsmen that were of any account over all England became this man's vassals as they were; and they all bowed themselves before him, and became his men, and swore him oaths of allegiance that they would against all other men be faithful to him.

"Thence he proceeded into the Isle of Wight; because he wished to go into Normandy, and so he afterwards did; though he first did according to his custom; he collected a very large sum from his people, wherever he could make any demand, whether with justice or otherwise.

"And the same year there was a very heavy season, and a swinkful and sorrowful year in England, in murrain of cattle, and corn and fruits were at a stand, and so much untowardness in the weather, as a man may not easily think; so tremendous was the thunder and lightning, that it killed many men; and it continually grew worse and worse with men."

So, the Domesday Book records who held the land and how it was used, and also includes information on how this had changed since the Norman Conquest in 1066. It is not a census of the population, and the individuals named in it are almost exclusively land-holders. (Source The National Archives)

The Domesday Book entry for Mimmine

Below is a short excerpt about Mimmine from the Domesday Book (more on this later), and below that a page covering Hertfordshire.

|

| The Domesday Book entry about Mimmine Image made available by Professor J.J.N. Palmer and George Slater Released under Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 |

|

| The Domesday Book entry about Hertfordshire Image made available by Professor J.J.N. Palmer and George Slater Released under Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 |

According to the Domesday Book, the Bishop of Chester held Mimmine (North Mymms) at the time the survey was carried out. The Victoria History Of The County of Hertford Vol 1, edited by William Page in 1902, has a chapter on the Domesday Survey, and on page 330 the book states that:

"Bishops could buy, inherit, or receive lands, like other men, in their private as apart from their official capacity. In this county for instance, the bishop of Chester held a manor at Mimms which he inherited from his father".

What the Mimmine Domesday records reveal

The Domesday Book is written in medieval English. Wikipedia, which has a page explaining the medieval land terms used at the time the book was compiled.

Below is the entry for Mimmine:

"The Bishop of CHESTER holds NORTH MYMMS. It was assessed TRE at 8 hides and 1 virgate; and now at 8 hides. There is land for 13 ploughs. In demesne [are] 4 hides, and there are 2 ploughs, and there can be a third. There 17 villans with 8 bordars have 10 ploughs. There are 3 cottars and 1 slave, pasture for the livestock, [and] woodland for 400 pigs. In all it is and was worth 8l; TRE 10l. 3 thegns, Queen Edith's men, held this manor and could sell."

So, what does it mean?

The date of the work - TRE

In the first lines the assessor writes: "It was assessed TRE"...

'TRE' is short for the Latin Tempore Regis Eduardi, which means "in the time of King Edward (the Confessor)". In the Domesday Book, the term appears in the entry for almost every manor, abbreviated as TRE. It signifies the date range 1042–1066.

So in this case the assessor is saying that, in the recent past (TRE), Mimmine contained more land (one virate more) than at the time the Domesday survey was carried out.

The land - hides, virgates, oxgangs and ploughs

The assessor then goes on to list Mimmine as being made up of eight hides and one virgate.

A hide was an English unit of land measurement, originally intended to represent the amount of land sufficient to support a household.

It was traditionally taken to be 120 acres (49 hectares), but was in fact a measure of value and tax assessment, including obligations for food-rent (feorm), maintenance and repair of bridges and fortifications, manpower for the army (fyrd), and (eventually) the geld land tax, an Anglo-Saxon land tax continued by the Normans used to assess the amount due based on the number of hides.

The hide's method of calculation is now obscure: different properties with the same hidage could vary greatly in extent, even in the same county, and there was a tendency for land producing £1 of income per year to be assessed at 1 hide. The Norman kings continued to use the unit for their tax assessments until the end of the 12th century.

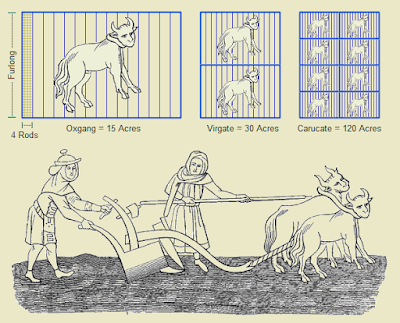

The virgate, yardland, or yard of land was an English unit of land. Primarily a measure of tax assessment rather than area, the virgate was usually (but not always) reckoned as a quarter of a hide and notionally (but seldom exactly) equal to 30 acres. It was equivalent to two oxgangs (an old land measurement based on land fertility and cultivation - see image below). You can read more about medieval land measurements in the appendices the foot of this article.

|

| Image by Paul Lacroix Released in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

The Domesday Book records that Mimmine had land for 13 ploughs. Also known as the carucate or carrucate, the term plough was a medieval unit of land area approximating the land a plough team of eight oxen could till in a single annual season.

The Mimmine Domesday Book entry continues with more detail, recording that:

"in demesne are four hides, two ploughs and room for a third".

In the feudal system, the demesne was all the land which was retained by a lord of the manor for his own use and support, and under his own management. This is to distinguish it from land sub-enfeoffed (give someone freehold property or land in exchange for their pledged service) by him to others as sub-tenants.

In England, royal demesne is the land held by the Crown, and ancient demesne is the legal term for the land held by the king at the time of the Domesday Book.

Below is a plan of a fictional mediaeval manor. The mustard-coloured areas are part of the demesne, the hatched (lined and shaded) areas part of the glebe (an area of land within an ecclesiastical parish used to support a parish priest.)

|

| Plan of a fictional mediaeval manor by William R. Shepherd Historical Atlas, New York, Henry Holt and Company, 1923 Image in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

The People - villans, bordars, cottars, and slaves

The assessor noted that working the land in Mimmine at the time of the survey were 17 villans, eight bordars who had 10 ploughs, along with three cottars and one slave working on the fields caring for the livestock, looking after the woodland, and tending to 400 pigs.

A villan was a rural farm worker who would be an unfree peasant who owed the lord of the manor labour services (two or three days per week), but who also farmed land for personal benefit. Villans were the wealthiest and most numerous of unfree peasants. They were also called villains or villeins.

A bordar was a feudal unfree peasant with less land than villans. They would be a tenant holding a cottage and usually a few acres of land at the will of the lord and bound to menial service.

A cottar, or cottager, was a peasant or farm laborer who occupied a cottage and sometimes a small holding of land usually in return for services. Sometimes the cottager would work on the holding of the villager.

A slave was man or woman who owed personal service to another, was not free to move home or work, or change allegiance. They were the property of the lord and had no land. The slave could not buy or to sell without permission.

The value - how much Mimmine was worth in 1086

Well, not a lot in today's money. The value of Mimmine was set at 8l at the time of the survey, although the assessor noted that under the reign of King Edward the Confessor it was worth 10l.

The lower case letter 'l' stands for pound, the oldest currency still in use. The Latin word for "pound" is libra. The £ or ₤ is a stylised writing of the letter L, a short way of writing libra.

Unfortunately, the only currency converter we could find in order to try to assess today's equivalent values is limited to calculations from 1270 onwards, almost 200 years after the Domesday Book was written. At that time, almost 200 years later, the National Archives Currency Converter estimates the value of Mimmine to be £5,838.

Law and order - provincial armies patrolling Mimmine

Mimmine was protected, according to the assessor preparing the Domesday Book entry, by three thegns, who were "Queen Edith's men" and who "held the manor and could sell".

Thegn means "one who serves", and was commonly used to describe either an aristocratic retainer of a king or nobleman in Anglo-Saxon England, or, as a class term, the majority of the aristocracy below the ranks of ealdormen and high-reeves.

An ealdorman was an appointee of the king who governed one or more shires or territories. The ealdorman was also responsible for leading his local fyrd (part-time army) in battle. But these armies owed their first allegiance to their ealdorman. Very often the support of one or more ealdormen could help a royal candidate to become king.

A high-reeve was an urban official whose job was to deputise for an ealdorman, and could lead provincial armies. Queen Edith was on the throne from 1045 to 1066. Her husband was Edward The Confessor.

Summing up

According to the Open Domesday, Mimmine had a "quite large population" compared to other Domesday settlements with 29 households. The total tax assessed (taking into account 8 units that were exempt) was high. Open Domesday says "relative to other Domesday settlements" Mimmine paid "a very large amount of tax".

So, plenty of land, a large population to work it, and a lucrative return for the king.

You can read more about the history of North Mymms (Mimmine) in Victoria County History of North Mymms, and learn more about the various names from Mimmine to Mymms in a piece written by Bill Killick.

Appendices

1: References used in the first extract from the translation of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles.

- (106)—and of Clave Kyrre, King of Norway. Vid. "Antiq. Celto-Scand".

- (107) Because there was a mutiny in the Danish fleet; which was carried to such a height, that the king, after his return to Denmark, was slain by his own subjects. Vid. "Antiq. Celto-Scand", also our "Chronicle" A.D. 1087.

- (108) i.e. a fourth part of an acre.

- (109) At Winchester; where the king held his court at Easter in the following year; and the survey was accordingly deposited there; whence it was called "Rotulus Wintoniae", and "Liber Wintoniae".

2: Understanding farm-derived units of measurement

- The rod is a historical unit of length equal to 5 1⁄2 yards. It may have originated from the typical length of a mediaeval ox-goad. There are 4 rods in one chain.

- The furlong (meaning furrow length) was the distance a team of oxen could plough without resting. This was standardised to be exactly 40 rods or 10 chains.

- An acre was the amount of land tillable by one man behind one ox in one day. Traditional acres were long and narrow due to the difficulty in turning the plough and the value of river front access.

- An oxgang was the amount of land tillable by one ox in a ploughing season. This could vary from village to village, but was typically around 15 acres.

- A virgate was the amount of land tillable by two oxen in a ploughing season.

- A carucate was the amount of land tillable by a team of eight oxen in a ploughing season. This was equal to 8 oxgangs or 4 virgates.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments on this piece

If you have any information to add to this item, please use the comment box below. We welcome input and are keen to update any piece with new research or information. Comments are pre-moderated, so there will be a delay before they go live. Thanks

Further information

If you require any further information relating to this, or any other item, please use the contact form, because we are unable to reply directly to you via this comment box. You can access it from the 'contact us' link at the top of any page on the website, at the bottom of the right hand side of the website, or at the bottom of any page.